Bruce McGechan literally wrote the book on exit planning in New Zealand. Below are the first four chapters of the book explaining the core concepts of exit planning from a New Zealand perspective.

Most Businesses Don’t Sell (Chapter 1)

I really liked my client. He was a hard-working entrepreneur who built a business that offered a unique health treatment.

His business was promising, offering a unique scientific health approach, it required licensing, was widely used in America and Australia but was yet to take off in New Zealand. He had started in Wellington and was expanding into Auckland. It had oodles of growth opportunity.

And yes, it had all sorts of issues—but didn’t every business?! I wanted to help this guy, sell his business, help him see more of his family and semi-retire.

I was early in my M&A career—and naïve.

Like a lawyer or accountant, I had decided I would help anyone who needed it. I thought I could help anyone—I was a highly qualified, an experienced businessman and director after all. Hubris.

It didn’t sell. To this day I feel awful about it, rather than helping this likeable, admirable fellow, I felt like I had failed him. Personally and professionally.

What I didn’t know then—and took me years to find out through hard-earned experience—was that only one in five private SME (Small Medium Enterprise) businesses sell (p.7, Snider, 2016).

“Only 1 in 5 private businesses sell.”

As I represented more and more businesses I was figuring this out of course. At first, I assumed it was to do with earnings size, so I only represented those companies with earnings of $1 million or more. Then I started to use other filters such as customer concentration, management in place, clear growth opportunities… the ratio got better but I was missing something.

Then I started to hear rumours about how it was even worse than that.

Of those business owners who exited their business, 75% profoundly regretted the decision within 12 months of exiting (Snider, 2017, p.9).

“75% of business owners who exit profoundly regret the decision within 12 months of exiting”

Digging into this I saw they regretted a) their life after exit (usually retirement) or b) they regretted the price and terms of the sale. For the most part, the regret was from a) the personal not b) the financial reasons.

And it got worse.

I saw that family businesses only successfully transition from the first to second generations 30% of the time. That 12% were successful from second to third, and 3% to the fourth generation. (p.7, Snider, 2017, quoting the Family Firm Institute). Even these “internal sales” were failing.

“30% of family businesses only successfully transition from the first to second generations”.

And worse.

Let’s do the numbers.

One US book and M&A organisation have had a bash for US numbers (chp. 1, Goodbread 2019, quoting Alliance of M&A Advisors and Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Report). Let’s apply those same estimates to NZ.

Let’s assume there are 10,000 mid-market NZ businesses (research estimates vary, see 21The Business Sale Process).

By 2030, about 7500 (75%) of mid-market businesses are expected to try and exit their business. Of these 750 (10%) will be deemed market-ready and only 450 (60%) of these market-ready businesses will sell.

Or put another way only 450 of the 10,000 mid-market businesses in NZ will sell by 2030. That’s 4% of total businesses and 6% of those businesses that want to sell. Swap that around, 94% of business owners will not be able to sell their business over the next decade.

“94% of business owners will not be able to sell their business over the next decade.”

And worse.

Of those that sell, just over half will have to sell with concessions. They’ll need to reduce their price, offer vendor financing or earnouts etc. Only 3% of mid-market business owners will sell for the original price. (Goodbread 2019).

The private capital markets and business sale industry was failing its clients.

And it was forecast to get worse.

Baby boomers own most of New Zealand SME businesses and those baby boomers are needing to retire. Many had thought about it in the 2000s but then the GFC struck and they deferred for a few years. Then they thought about in the last few years and Covid19 struck.

These business owners faced a perceived drop in the value of their business and other financial assets and delayed their sale. Each time a cohort of business owners have deferred their sale the backlog of future baby boomer businesses for sale has increased. Then the economy has picked up, dividends have increased, and they have further delayed any exit.

During the last decade, the median age for a baby boomer has increased from the early sixties to early seventies. This decade the median age will increase to the early eighties.

NZ business media periodically report on a proverbial wall of business sales crashing on New Zealand like a tsunami wave flooding the market. I think this misses the dynamic of a business lifecycle. I think the analogy is incorrect, rather than a tsunami of business, it is more like a sand dune of businesses that get slowly eroded by waves of the “5Ds”.

The 5 Ds are Death, Disability, Divorce, Disagreement and Distress/Disaster. Half of all business owners exit their businesses through the 5 Ds (Christman 2015, p.18).

“50% of business owners exit their businesses through the 5 Ds: Death, Disability, Divorce, Distress, and Disagreement.”

I was involved in a tourism aircraft company. The CEO was the minority shareholder and had tragically passed away. His surviving spouse and the majority shareholder intensely disliked each other. The business was paralysed for many years due to the CEO’s Death and shareholder Disagreement.

When an owner is Divorced they often need to sell the business to pay the divorce settlement. Or the business is owner-dependant, and the owner becomes Disabled through stroke or accident resulting in weeks in hospital and the business disintegrating.

On average, about 80% of a business owner’s wealth is tied up in their business (Goodbread 2019). If the 5Ds strike then a business owner can see their net worth collapsing by 80%. Imagine if 80% of wealth held as term deposits by a finance company disappeared? The investor would be—and have been—devastated.

“80% of a business owner’s wealth is tied up in their business”

The business owner has spent their life building their business. They are now feeling their age and they know they need to retire. They quite reasonably expected to sell to a third party or have their children or management succeed them. Yet the chances are they will not sell, will regret selling, or the business will not survive their children.

There is a better way. It’s called “Exit Planning”.

Successful Transition from Business Owner to Retirement (Chapter 2)

Exit planning sprung from two mid-market M&A Advisors in the US facing the same dilemma 20 years ago. Their names were Peter Christman and Richard Jackim, the founders of the exit planning approach.

Just like me, in another country two decades ago, they too were seeing the tragedy of business owners expecting to happily retire but instead didn’t sell or ‘profoundly regretted’ the sale.

Peter Christman’s ‘wake-up call’ was when he realised that his business owner clients were losing most of their business wealth to the US government in various taxes. He saw with proper tax and estate planning they could be keeping much more of their wealth.

He was also seeing owners not being sure what to do with the cash they were receiving from the business sale. As he puts it, “if you don’t have a plan for your money you can trust that someone else does”.

Wealth was being lost through poor tax planning and then spent in ways that did not support the business owner’s family goals.

Like me, Peter was an M&A Advisor, he realised he needed to build a team around his clients that could help prepare the client for their exit. Tax and Wealth advisors formed the first two parts of that team.

He then looked at the client’s businesses.

He was proud of his business sale process but he still saw that the companies could have sold for more if only they had done several things to increase its value. The business itself was being run to support their lifestyle rather than to build value for a future buyer. If they could run the business from a value management point of view, from a third-party acquirer’s point of view, then the business price and terms could substantially improve.

A large part of exit planning is about increasing the value of the company and then keeping more of that value for yourself on sale.

“Exit planning is about increasing the value of the company and then keeping more of that value for yourself on sale.”

In the US, Peter read about how demographic expert and economist Robert Avery predicted how baby boomers would transfer $10 trillion to later generations, and that most of that wealth was held in private businesses.

Together with Richard Jackim, he wrote a book called “The $10 Trillion Opportunity” in 2005 based on the size of that challenge. The book was his first step in changing the industry, together with a later book he wrote called “The Master Plan”. This set the foundation for exit planning.

Peter and Richard’s foundational idea is the 3-legged stool. Leg One is maximising company value. Leg Two is personal financial planning. Leg Three is the retirement plan or ‘Life Plan’. Together they are known as the Master Plan.

In order for the stool to be stable, each leg has to be equally strong and long. If one leg is weak or shorter then the stool—the Master Plan—is unstable.

Remember our exit planning aim here is to avoid you being one of the 75% who profoundly regrets selling their business. This isn’t just maximising business value, though that’s important, but preparing your family and yourself for your retirement. Have I mentioned your spouse is key to this process yet?

Back to Peter Christman. Having written the book, his next step was co-founding the Exit Planning Institute (EPI) with the aim of training and certifying exit planning advisors. It has now trained, tested and certified advisors from all around the world, including myself.

In 2012, Peter sold EPI to Christopher Snider, a fellow CEPA. Chris Snider had extensive operational experience in many fast-growing private companies as a manager, director and investor.

Using Peter’s foundational work around planning Chris then developed the methodology to put both process and execution to Peter’s exit planning foundations.

As Chris puts it, exit planning is actually a good business strategy that focuses on increase the valuation of the company while aligning the business, personal and financial goals.

“Exit planning is actually a good business strategy that focuses on increase the valuation of the company while aligning the business, personal and financial goals.”

This methodology is called the Value Acceleration Methodology©, the best practice approach in our industry.

He also made 90-day action ‘sprints’ at the heart of the methodology. He wanted business owners to see profits, business valuation and their wealth increase every 90 days. Action right now, every day, he calls its “ruthless execution”.

My role is to change the New Zealand industry by educating and assisting business owners and the wider industry. But my firm and I can’t do this by ourselves. We also need to educate the team of advisors that are needed to help the business owner transition to retirement including wealth advisors, accountants, and lawyers. Indeed, all of these people are an exit planner and in the US many of them are fellow CEPAs.

The Exit Planning Institute (EPI), the international association run by Chris Snider, formally defines exit planning as,

“Exit Planning combines the plan, concept, effort and process into a clear, simple strategy to build a business that is transferable through strong human, structural, customer, and social capital. The future of you, your family, and your business are addressed by exit planning through creating value today.”

As you read this book the parts of the EPI definition will come together and we’ll explain especially the meaning of “transferable”, (intangible) “capital”, “family” and “creating value today”.

Chris Snider, puts it more simply, “exit planning is simply good business strategy”.

The outcomes you’d expect from the Value Acceleration Methodology© is to:

- make more money now

- give you independence from your business

- reduce risks

- increase your wealth by as much as 400%-500%

- and empower your teams or children to take the business to next level.

“Increase your wealth by as much as 400%-500%”

“Increase your wealth by 400%-500%, wait what!?”, I hear you say. About 80-90% of a business owner’s wealth is usually in the business (Christman, 2015). In this book, we will walk through how to increase that value through something called the multiple, more on this later.

From an exit planning point of view, there are two types of businesses: lifestyle businesses and value creators. The lifestyle business is a good business that generates good earnings—but it is not transferable.

The value creator business is seen as an asset and makes a good income too. They are operating at best-in-class performance levels for their industry—and they are transferable.

Most businesses are lifestyle and cannot be transferred to a new owner. Remember the statistic of 80% of businesses not selling or “transitioning”, they fall into this category.

This is not a judgement about lifestyle, that is the owner’s prerogative, really it’s about whether a lifestyle business owner can become a value creator owner. Can they change their paradigm, can they see “the way we see the problem is the problem” to quote Steven Covey.

Let’s help you find out. The next chapter covers the core concepts of exit planning.

The Core Concepts (Chapter 3)

There are four core concepts in exit planning.

We’ve already read about the first one, the three-legged stool, the other three are the five stages of value maturity, the four capitals and relentless execution. These are the basis of the methodology.

Three-Legged Stool

The three-legged stool I covered in the previous chapter. Leg One is maximising company value. Leg Two is personal financial planning. Leg Three is personal planning.

Together they are known as the Master Plan. In order for the stool to be stable, each leg has to be equally strong and long. If one leg is weak or shorter then the stool—the Master Plan—is unstable.

Leg One is maximising company value. Leg Two is personal financial planning. Leg Three is personal planning…If one leg is weak or shorter then the stool—the Master Plan—is unstable.

In Leg One, maximising company value, a thorough analysis of the business attractiveness and exit readiness is conducted. An initial appraisal of value is made by adjusting earnings and comparing similar business sales in the private capital markets. This shows the current business value, the strengths and weaknesses, the gaps (see below) between the business value and its peers, and a plan to close those gaps

In Leg Two, personal financial planning is at least started. The objective is to know the owner’s and family’s goals and what lump sum is required to fund them. Tax and estate planning would be conducted. An appointment of a wealth advisor (technically a financial advisor with a license and experience in financial advice and investment planning) is critical in the exit planning process.

In Leg Three, personal planning is the retirement plan for a baby boomer or life-after-exit plan for a younger business owner. They’ve been working 40-60 hours a week, what are they going to do when they sell the business? This is a key solution to the problem of 75% of business owners profoundly regretting their exit.

All are equally important but the one that is most often not addressed is the personal planning.

Five stages of Value Maturity

The word ‘Value’ is thrown around usually in the context of adding value. Frankly, it’s corporate jargon, so let’s be very specific about what we mean by value.

At its simplest Value is the profit from a particular strategy. If you acquire a new customer who has revenue of $2 million pa, gross profit of $1 million, has selling and admin costs associated with the customer of $250,000, then the value of that new customer is $750,000.

But it also means the value of the company, it’s valuation. This is what we really mean.

The value equation looks like this:

Value = Earnings times Multiple.

For this section, I’ll use this simple but famous formula. I’ll cover valuation in detail in 6Enterprise Value Assessment from an exit planning point of view and 25Business Valuation from a technical business valuation point of view.

For example, if a company has earnings (usually adjusted EBITDA) of $3 million and a multiple of 2.5x, then the company’s value is $7.5 million.

Value = Earnings times Multiple.

Earnings are important but the Multiple is critical to maximising business valuation.

In the example, you can increase your earnings from $3 million to $3.5 million then the company’s value is now 2.5 times $3.5 million or $8.75 million. All other things being equal the company value has now increased by $1.25 million.

However, instead of increasing profits, you invest in your company resulting in an investor increasing their multiple analysis from 2.5x to 4x. Now your company’s value is 4 times $3 million or $12 million, a $3.25 million increase.

And if you increase both? $3.5 million of earnings times by 4x multiple or $14 million, close to doubling your company’s value.

The multiple is more important to increasing the value of the company than the earnings.

I’ll return to this key formula throughout this book, it’s at the heart of Value Acceleration Methodology ©, when we say you’re leaving wealth the table, we’re talking 200%+ not 20%.

“When we say you’re leaving wealth the table, we’re talking 200%+ not 20%”

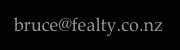

There are five stages to creating this value: Identity, Protect, Build, Harvest, and Manage, see below.

Figure Value Maturity Index: The Five Stages of Value.

Source: Snider, 2015, p.73

In the first stage, we Identify the current value of the business.

We benchmark it against others in the industry in what’s known as an Enterprise Value Assessment.

We’ll cover how we do this in 6Enterprise Value Assessment but in short, we look at where your business sits versus comparable business sales and consider the risk of the future earnings. We also identify the personal planning and financial planning situation.

In the second stage, we Protect what you have.

The less risk to future earnings, the higher the multiple. This includes the risk analysis and contingency planning for key people, owner dependence, large customers, lack of supplier agreements, business interruption, technology and more.

But it’s not just business risk, it’s also personal risk particularly the 5Ds: Death, Disability, Divorce, Distress and Disagreement.

There is a 50% chance (Christman 2015, p.18) that one of these will happen to you. Most baby boomer businesses in New Zealand will simply fade away due to the 5Ds—along with 80% of the family wealth.

Your wealth or financial advisor will help you reduce your financial and personal risks. Your personal assets may not be diversified (market risk) and you may not be insured (death, disability/health).

Lastly, if you want to grow the value of your business, you’ll need to undertake additional risks. Let’s reduce or transfer risks to other parties before undertaking new risks.

Note that instead of growing the business you may decide it’s time to sell the business. The Value Acceleration Methodology© helps you make this decision every 90 days.

Having protected the business and decided to grow it, the third stage is to Build.

This is where we really build value.

A long term view is taken to build the intangible capital. The aim is to increase the multiple as well as earnings through using the Value Acceleration Methodology©.

Building the four Cs: Human Capital, Structural Capital, Customer Capital, and Social Capital is critical to increasing the business value. More on this in the next section.

At some stage, the owner will wish to Harvest the value.

We consider your exit options including selling to a business partner, employees/managers or a family. It may be best to sell a part to a private equity firm or all of the business to a strategic buyer.

You may even have an orderly liquidation, a rare option in exit planning but a valid option. Very few mid-market business list on the stock market, if the business value is $100 million it might be an option but really it should be $200+ million in the New Zealand context.

Research shows two-thirds of business owners are not aware of their options (EPI, 2013). Indeed it may not even be your best option to sell to a third party. Note that even if your children are taking over it is best if they purchased the business rather than it be gifted (Deans, 2014). I cover your options in Chapter 15 Exit Options.

Having harvested the value in your business, it’s time to Manage that Value.

You now have the wealth to implement your personal plan, family wealth rather than just wealth locked in the business.

One final point about Value. You may need to spend cash to increase Value so there may be tension in your mind about increasing Value while reducing earnings. This isn’t quite right, you can have both but first, you must focus on Value.

How do we build value? It is all about the 4Cs.

The Four Capitals (4Cs)

The business sales data shows that on average 80% of the business value is in intangible value, the rest being tangible assets.

The intangible value is split between Human capital, Structural capital, Customer capital and Social capital.

“Intangible value is split between Human capital, Structural capital, Customer capital and Social capital.”

Human capital is the value of your talent: the management and the staff. The high performing team in an industry will outperform the poor performing team.

The famous comment by Jim Collins in “First Who, Then What” (Collins, 2001), is the idea to get great people, put them in the right position, and unload the wrong people. He goes on to say, “great vision without great people is irrelevant”. A (in)famous execution of a great people strategy is Jack Welch’s “Vitality Curve” where the bottom 10% of managers are replaced by those with the potential to be top 20 managers.

Customer capital is the value of your customers. How deep and entangled are those relationships, are there multi-year contracts, what about reoccurring revenue? Is there any customer concentration? A customer that makes up 10% of revenue is concerning, a customer that makes up 70% of revenue may make the business unsaleable. Critically, are these relationships transferable (see the Grapester case study)?

The answer is of course diversification of the customer base but this may be difficult in the short term. In which case writing a sales plan is the minimum. Preferably entering into multi-year transferable contracts and entangling the customer’s business with your own are two demonstrable ways to build customer capital.

Structural capital is infrastructure and its transferability. Think of the processes and systems that support the business. This includes the technology, machinery and facilities that support your team to serve their customers.

Again, critically, are these transferable? If they remain in the owner’s and employee’s heads or poorly document then they are not. The knowledge held by the business needs to be transferred to the new owner. A large part of the Prepare part of the Value Acceleration Methodology (c) is about proving to buyers this capital can be transferred.

Social capital is the culture of the business. You arrive at great Social capital having built the other three capitals. It incorporates many things including the teamwork and cadence of activity, the brand, the vibe when you walk in.

Let’s go back to the business value formula:

Value = Earnings times Multiple.

The business owner has the ability to control earnings but Value Acceleration is really done in the Multiple part of the value equation.

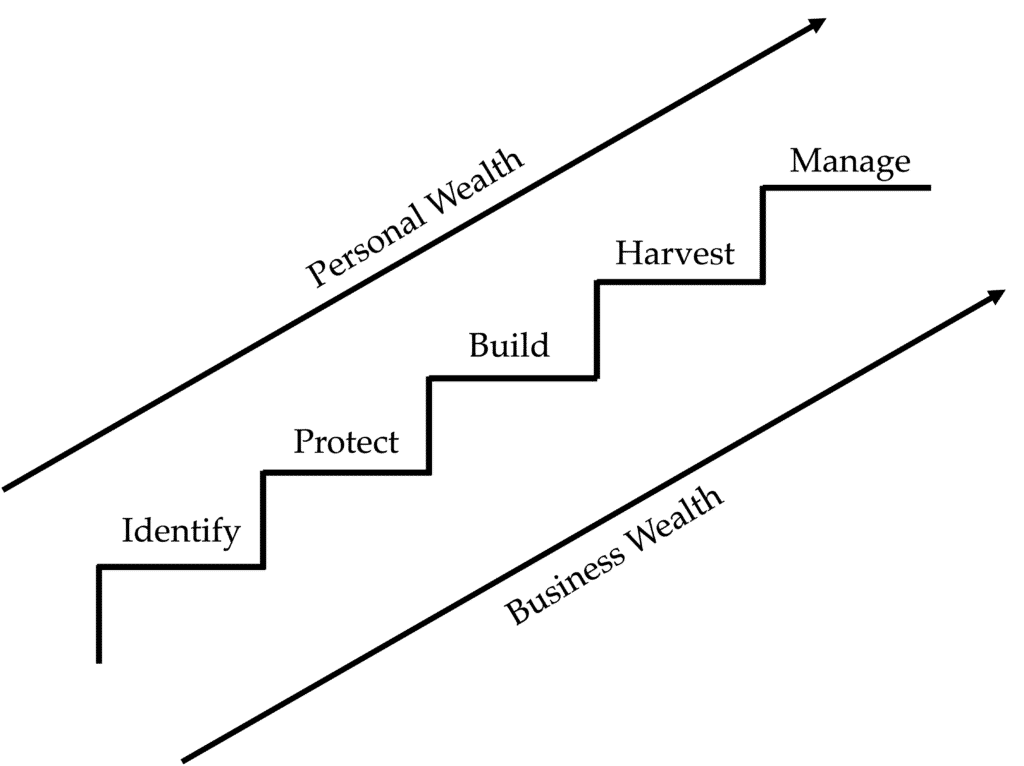

The private market sets Multiple ranges for particular industries, some industries have a wider range (better industries usually), others narrower. Think of a bell curve, see below.

Figure Range of Value Bell Curve

The numbers 1 to 6 and the percentages form of a scoring system, see later in this section.

The owners can’t control the Multiple—but they can control where they place in that range. Where they place depends on the strength of their four Cs. The stronger the 4 Cs the higher your business is in that Multiple range.

“Owners can’t control the Multiple—but they can control where they place in that range. Where they place depends on the strength of their four Cs.”

Many companies have weak 4Cs, and either get a price in the lower end of the Multiple range—or don’t sell. On the other end of the scale are those with strong 4Cs, the best-in-class companies in their industry: great talent, deep customer relationships, strong IP, niche products etc. Most companies cluster in the middle of that bell curve around the average.

A Certified Exit Planning Advisor (CEPA) uses questionnaires to score companies to understand where they are in that range. We score the business by using the questions to identify business attractiveness and readiness for sale. If that score is below average you’ll get a below-average multiple (or not sell), above-average leads to an above-average multiple for your industry.

We can also look at benchmarks for the industry to understand where you fit versus other businesses and any potential upside in profit.

Together, the scoring and the benchmarks place you somewhere on that bell curve. CEPAs have found that it’s the intangible assets, the 4Cs, that drive multiples above 2x.

Value Acceleration is about building your intangible assets so you can increase the multiple which in turn increases your business value.

There are several questionnaires we can use to measure this intangible value. They all help a CEPA score all the three legs of the master plan stool.

I prefer those that use a six-point scoring system: six is perfect, five is best-in-class for the industry, four is slightly above average, three is slightly below average (purposely there is no exact average), two is probably below average (thought about but with nothing written), and one is nothing at all.

The idea here is to not just talk about a plan or have the knowledge but to score the current intangible value, work out what can be improved and then action those improvements.

Let’s say you are scoring one of the capitals and the questionnaire has five questions for that capital. Each question is worth six points or a total of 30 points. You scored yourself a total of 13 points, so your score is 13/30 points or 43%.

In this system, any score below 50% is a red flag and an average is 58%. This business has room for improvement and may not be ready for sale. If it did go to market it probably would not sell and would certainly sell for a price that left the business owner’s wealth on the table.

Each question that scored poorly would be an area to improve.

For example, it might be dependence on the owner, lack of experience in the management team, or lack of skill in the staff. An experienced GM may be hired and a training programme put in place for key staff. The scoring would then show a higher percentage, moving the company up the multiple range. By hiring better people, you do not just increase the Value through the multiple but better people may increase your sales or efficiency thereby also increasing your earnings. Focusing on Value should also lead to higher Profit.

Relentless Execution

Perhaps one of the biggest changes in exit planning from Chris Snyder is focusing on execution, not just planning.

Chris calls this “Ruthless Execution”. He is a little cynical about business strategy that stimulates your mind but doesn’t provide you with a process on how to do it.

There are four components to Relentless Execution: Vision, Alignment, Accountability and Rhythm.

Firstly we need a clear and compelling Vision from the owner and owner’s family. Then we need to articulate that Vision to the team and Align all the resources to do it. It’s about creating an action plan.

Accountability is holding the team (and the owner) to their promises under the action plan. It may be to do with individual performance but is probably more a resource or process issue that needs to be fixed.

Rhythm happens once you have vision, alignment and accountability. It’s the result of the steady practice of Relentless Execution. Like a golf swing, steady practice builds rhythm or cadence over repeated projects.

We also use various tools to ensure Relentless Execution.

The first is workshops, not meetings. Workshops are more collaborative and have a set time of usually 2-3 hours. The methodology below is based on deliverables from 2-3 hour workshops.

At workshops, the decision-makers participate and also help get buy-in.

The next is 90 days sprints, this is “a continual loop of prioritising, executing, measuring, reconnecting and recalibrating every 90 days” (Snider, 2016). You’ll see these mentioned below in the Prepare process of the methodology.

No project scope is longer than 90 days. If it is, then it needs to be split up. We need to be acting not thinking given the owner wants to transition the business soon.

We also need to ensure that the managers have the resource and time to implement the plan in 90 days. If not, then they need to reduce their workload or reduce their scope in a project.

Every 90 days we reprioritise what we’re doing. In theory, these 90 days sprints could happen for many years, especially if the business is increasing its Value and Profit. But at the end of one of the sprints, the owner will say they want to consider exiting rather than continuing down the growth track.

What say the business owner has only one year before wanting to exit? Then you focus on Protect, protecting what you have, you don’t have time to Build the business. You may however mitigate risk thereby building Value if you make the business transferable by focusing on the 4Cs.

So how do we implement these concepts?

The Value Acceleration Methodology©

Here is how Chris (Snider, 2016) puts it,

“Value Acceleration is a proven process that focuses on value growth, and aligning business, personal, and financial goals.

•Integrates the three legs into one Master Plan

•Is grounded in action

•Promotes the use of teams in an engaging process

•Creates a roadmap to success

•Provides owner key deliverables and metrics

•Creates a Leap in Value”

The methodology uses a gating process. You can’t pass through a gate until you do certain things. This is to ensure the next stage of the process is successful.

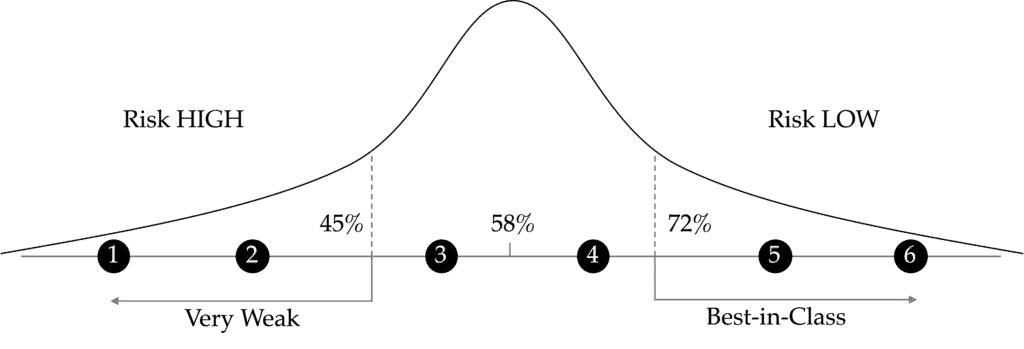

We have three gates: Discover, Prepare and Decide. Think of gates as a process with a milestone. There are actions that need to take place following a process and then the milestone is when those actions have been completed. See Figure #fig(VAM) below.

Figure Value Acceleration Methodology©

Source and copyright: EPI.

Let’s step through the methodology by the three gates Discover, Prepare and Decide.

Discover

The Discover process is identifying what you already have. It has the major steps

•Business Valuation and Personal, Financial, Business Assessments, known together as the Enterprise Value Assessment

•Prioritised Action Plan.

Business values trade in an industry range of multiples decided by the market. Where you sit in that range depends on:

•financial analysis of your business and industry benchmarks

•how attractive your business is to a buyer

•how ready your business is to sell.

It’s called an Enterprise Value Assessment and gives you clarity as to how much wealth you may be leaving on the table, the risks and the growth opportunities.

The Prioritised Action Plan is at the end of the Discover phase and most of the time it will “trigger” the business owner into taking action.

The business owner is now in the position to decide whether the business should be sold, de-risked and/or grown. They have clarity as to where they sit in relation to their personal goals, personal financial situation and the current value of the business. The three legs of the stool.

They could choose at this point to do nothing, but most business owners are struck by the opportunity to at least protect their family if not grow and realise their wealth.

Again, they get clarity. They know the strengths and weaknesses, they have an action plan to address those weaknesses.

Prepare

The Prepare process is implementing that prioritised action plan.

We now understand what the personal goals are, the wealth required to achieve them, and how much a business sale can contribute to the family wealth. We have an action plan to implement.

The CEPA “quarterback” or project manager now works with the business owner to form two new teams. One team focuses on the personal and financial planning, led by a wealth manager, and one team focused on business improvements led by a ‘value’ or business advisor.

It may be that the personal and business advisors are CEPAs but currently, in New Zealand this is unlikely. In the meantime, I am educating wealth advisors on exit planning, ideally before commencing a client project. Certainly, I am encouraging them to become a CEPA as many of their counterparts are in the US.

The first two steps of Prepare, Personal and Financial Planning and Business Improvements, are encapsulated by a box, see Figure #fig(VAM) above. This is because the team leaders need to be talking to each other to ensure the three legs of the stool are equally addressed as they go through the process.

The Prepare process is iterative. Every 90 days we ask the owner the big question…

Decide

Do you want to grow or exit? The Decide process is deciding whether to keep growing or to exit.

If you decide to keep the business then we will need to undertake more advanced value acceleration. Projects that may require capital expenditure and even capital raising.

If you decide to sell the business then we will continue to de-risk the business and getting it ready for sale. Reducing debt and considering which exit option is the best for the owner and owner’s family.

Value Maturity and Value Acceleration Methodology©

The gates of the methodology line up with the stages of Value Maturity. The Discover Gate is the Value Maturity approach the “Identify” stage.

The second and third stages of Value Maturity, Protect and Build, are in Prepare. The fourth stage, Harvest, is in Decide.

The fifth stage, Manage, is the completion of the process and is perhaps represents the whole methodology rather than a gate.

The next core concept is about the Gaps covered in the next chapter.

The Gaps: Wealth, Value and Profit (Chapter 4)

These are three fundamental numbers a business owner needs to understand: the Wealth Gap, the Profit Gap and the Value Gap.

The Wealth Gap

The Wealth Gap, see Figure WealthGap below, is the difference between what personal financial wealth the business owner has outside the business versus what lump sum they need at retirement to achieve their personal goals.

The owner and family will need a retirement income but also funds for travel, a new home, a legacy for the kids and grandchildren etc. The wealth advisor helps them work out the total wealth they want by summing the cost of each of the family’s goals. Note this total wealth could be two figures: what they need, and what they want. Perhaps the business sale will only be able to fund what they need, the lower figure.

These goals are based on the family’s personal plan and are probably calculated by their wealth adviser. A wealth goal is the sum of the wealth required at exit to achieve their personal plan. The wealth gap is the gap between the wealth goal and current personal assets, it is what business sale needs to bridge.

“The Wealth Gap is the business sale amount required to fund the retirement goals of the business owner.”

For example, they may need a retirement income of $300,000pa for the owner and spouse to live as envisioned during personal planning. Their wealth advisor calculates they need $6 million to be invested as a lump sum at retirement. A rule of thumb, inaccurate as it might be (I recommend you always use a financial advisor), is you take your desired retirement income and divide it by 4%. Following this rule, $300,000 divided by 4% = $7.5 million, is the lump sum required to be invested at a retirement age of say 65 years.

In the case of younger owners, they may not have retirement goals but they still have goals that need to be funded and the same concept applies.

Figure Wealth Gap

The issue often is that the income from the business is much higher than the income from a diversified portfolio of shares and bonds. The owner may be getting a 30% return on their business but that will drop to less than 8% when diversified—but it will be much safer than being exposed to a single asset, the business.

The owner or spouse will then say there is no way I can live on that amount, there is a gap between the income from their current single high-risk high-return asset versus the income from a much lower-risk diversified portfolio. Business owners are different and they need wealth advisors who understand their particular issues.

The business owner probably has a gap—a Wealth Gap.

The Profit Gap

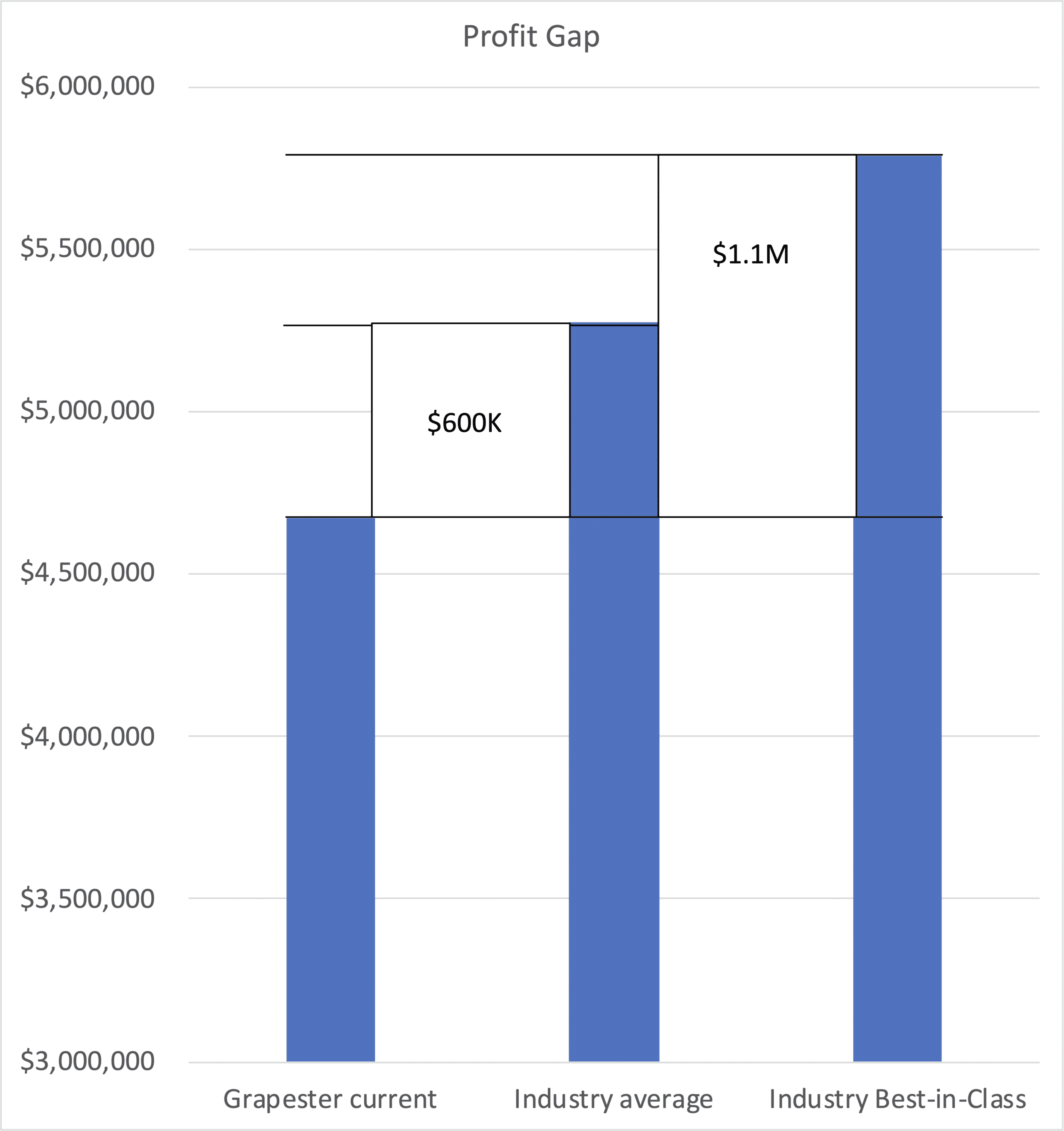

The Profit Gap is the difference between what the business’s current earnings are versus industry best-in-class businesses (assuming the current level of revenue).

It is a measure of the EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest Tax Depreciation Amortisation) as a percentage of revenue, versus the industry best-in-class EBITDA % of revenue.

If the business owner can achieve the same EBITDA % of revenue benchmark as the best-in-class company then their profit will increase, assuming no change in revenue.

“The Profit Gap is the difference between what the business’s current earnings are versus industry best-in-class businesses.”

For example, if a business has $30 million revenue and 7.5% EBITDA % to revenue, then it has EBITDA of $2.25 million. Best-in-class companies achieve 12.5% EBITDA, applying 12.5% to $30 million shows a best-in-class company would make $3.75 million EBITDA off that revenue. The Profit Gap is $3.75 million best-in-class less $2.25 million for the business owner, or $1.5 million. That is how much additional earnings the company could be making if they were operating at best-in-class levels. See figure below.

Figure Case Study Profit Gap

Source: Grapester Enterprise Value Assessment Case Study Profit Gap in Chapter 5

It may be that the business owner thinks that best-in-class is too much of a reach and that the average is a more realistic goal. Perhaps the average is 10% EBITDA to revenue and if you work that through the profit gap would be $0.75 million.

See Step 3 in the case study in Grapester Enterprise Value Assessment for the worked-through example.

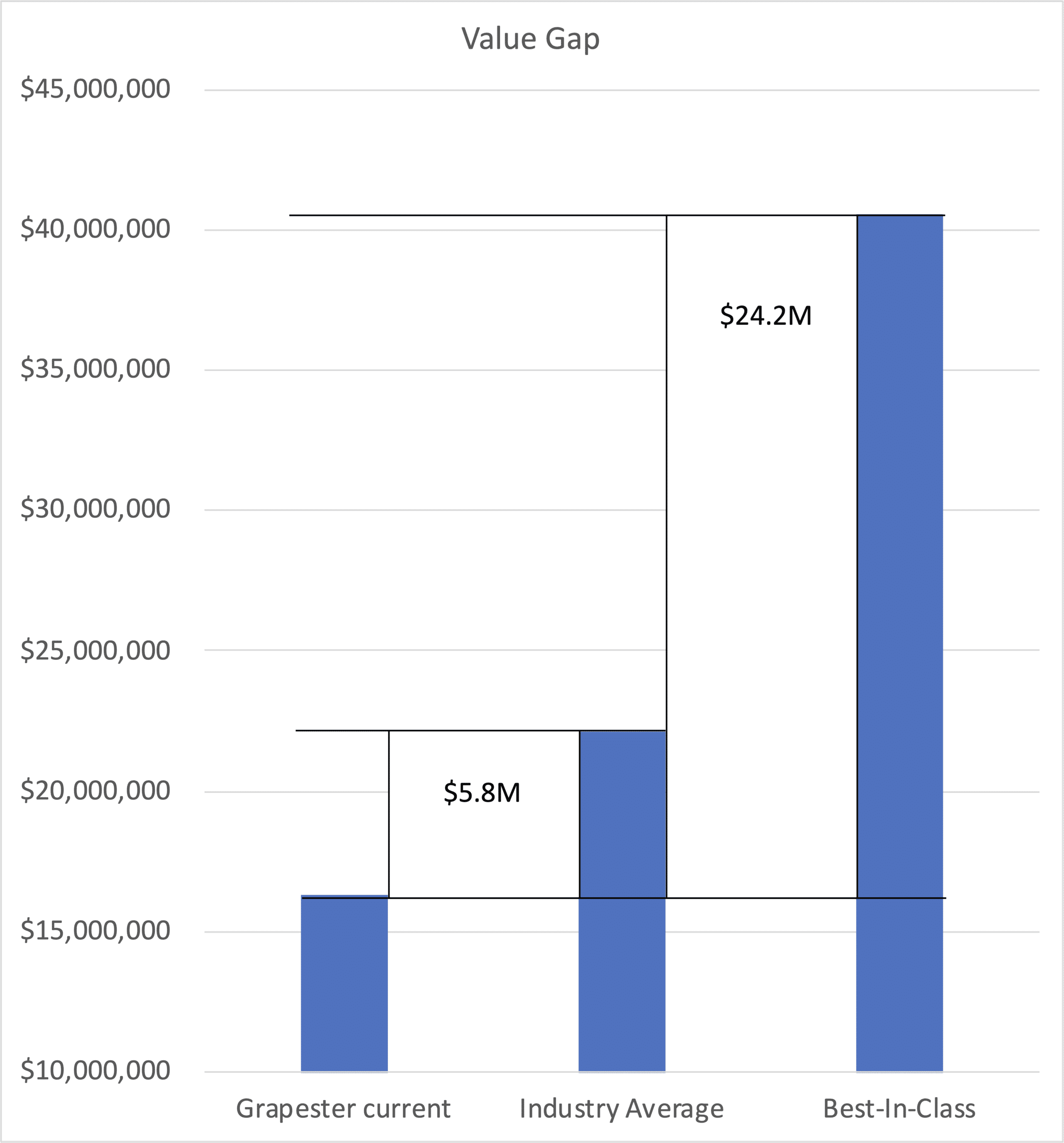

The Value Gap

The Value Gap is the current valuation versus what the business would be operating at if best-in-class for the industry (assuming the current level of revenue).

The measure of Value is the Multiple. In any industry, there is a multiple range set by the private capital markets. Let’s say that in this industry the average is 3.5x, best-in-class is being valued at a 5.5x multiple, but the owner’s business has been valued at a 2.5x multiple.

“The Value Gap is the current valuation versus what the business would be operating at if best-in-class for the industry.”

Using the example above, the owner’s business value equals 2.5x times $2.25 million or $5.625 million.

The best-in-class is valued at 5.5x times $3.75 million or $20.625 million.

The Value Gap is $15 million, that is $20.625 million less $5.625 million. This is about 367% more than the business owner’s current value, see figure below.

Figure Case Study Value Gap Graph

Source: Grapester Enterprise Value Assessment Case Study Value Gap in Chapter 5.

Now the owner might say that the Value at the industry average is all the family needs to achieve their goals. Average Multiple is 3.5x, average EBITDA from above is $3 million, for a total of $10.5 million. The Value Gap now being ‘only’ $4.875 million or almost double the current valuation.

See Step 5 in the case study in Enterprise Value Assessment (Chapter 6) for how this is calculated.

The Gaps

Why does the best-in-class company have the higher Multiple? It goes back to the 4Cs. They have better human, structural, customer and social capital. And because they have a better company they are also generating higher profit from the same revenue.

This exponential growth in Value not only increases the price a business owner may get but also makes the company more transferable.

The overall aim is always to avoid the business owner ‘profoundly regretting’ the business sale 12 months after the transition. Closing the Wealth, Profit and Value gaps by investing in the 4Cs is a key way to avoid this regret.

“Closing the Wealth, Profit and Value gaps by investing in the 4Cs is a key way to avoid ‘profoundly regretting’ the business sale.”

You can also now see why the wealth advisor and the CEPA need to be working together. The wealth adviser tells the business owner they need $10 million to achieve their personal goals. He also tells the CEPA.

The CEPA tells the business owner that the company is worth $5 million. He also tells the wealth advisor.

At that stage the personal plan can be reconsidered, what are needs vs wants. Or the business owner can focus on creating value to close the Value Gap and not change their personal goals. This iteration gives clarity to the exit process.

Let’s first go through the illustrative case study and then dig into the process.

Want to read the following chapters? Please purchase How to Sell a New Zealand Business with ‘No Regrets’.