Bruce McGechan literally wrote the book on selling a business in New Zealand. Below is the introductory chapter of Part II of the book explaining the business sales process from a New Zealand perspective.

The Business Sale Process (Chapter 21)

Introduction

This chapter gives an overview of the process of selling a business to a third party whether it be a 100% sale or a partial sale. It steps through each major part of the process. The following chapters go into a little more depth of each part.

Intermediary Advisor

The business owner first appoints an intermediary. See Chapter 23 The Advisors on more about these advisors and their engagement.

In theory, you could do it yourself, and most small businesses seem to do that based on analysis of business-for-sale website listings. The problem is you lose the ability to conduct an orderly auction.

Which intermediary depends on the size of the business. The smaller the business the more likely the owner will do it themselves or appoint a business broker. Mid-market businesses will almost always seek an advisor, most likely an M&A advisor. Larger companies will see advisors like the stockbroker firms who can also prepare companies for an IPO. I will use “M&A advisor” as shorthand for the different intermediaries.

On appointment, the M&A advisor and business owner discuss timeframes, business value, management continuity, non-compete, confidentiality process and the owner’s sales objectives. They talk through the strengths and weaknesses, and growth opportunities. They discuss different sales processes and whether to focus on a few buyers or many.

If a CEPA has not been involved then this will be multiple meetings, emails and phone calls as the M&A advisor educates the business owner, and the business owner explains the company.

If a CEPA is involved the business owner is prepared for sale, needs less preparation by the M&A Advisor and has been educated about the sale process. Of course, they will have questions but they have a rolling start to this long process.

Research and Analysis

The M&A advisor will value the company in a range. The advisor will prepare a three statement (P&L, Balance Sheet, Cash Flow) financial model to show not just historical figures but also forecast the flow of cash through the business. They will also recommend an EBITDA figure adjusted for owner benefits or non-recurring expenses.

The advisor will collect transaction comparable multiples and place the business in that range. They will assess the risk of the company and estimate a discount rate for use as a cap rate and/or a discounted cash flow rate (see Business Valuation). They will provide an opinion on business value.

A “Buyers’ List” will be assembled. There are two general types of buyers in mid (and large) market deals: 1) strategic buyers and 2) financial buyers.

Strategic buyers are within the industry and are driven by the desire to grow e.g. large competitors, customers and suppliers often from outside the geography. They are also called “trade” buyers.

Financial buyers bring capital and have the desire to make a good return on their investment. For example, private equity, family offices and individuals.

Small businesses will likely target private buyers. These buyers are often impossible to identify requiring advertising to get them to express interest. Small business sales also don’t often have financial modelling of cash flow nor advanced valuation methods. They will add all “seller’s discretionary earnings” to the adjusted earnings figure including one shareholder’s wage. In NZ we call this EBPITDA, Earnings Before Proprietor’s wages Interest Tax Depreciation and Amortisation.

Some private buyers who can’t be identified are wealthy enough to purchase a (lower) mid-market business resulting in some mid-market businesses also using advertising to attract buyers. A judgement call will need to be made by the M&A advisor and advice given to the owner.

Note that the advisors, the business owner, managers, advisors and board will all brainstorm a list of possible buyers: strategic, financial, in the region, in NZ and overseas.

Documentation Preparation

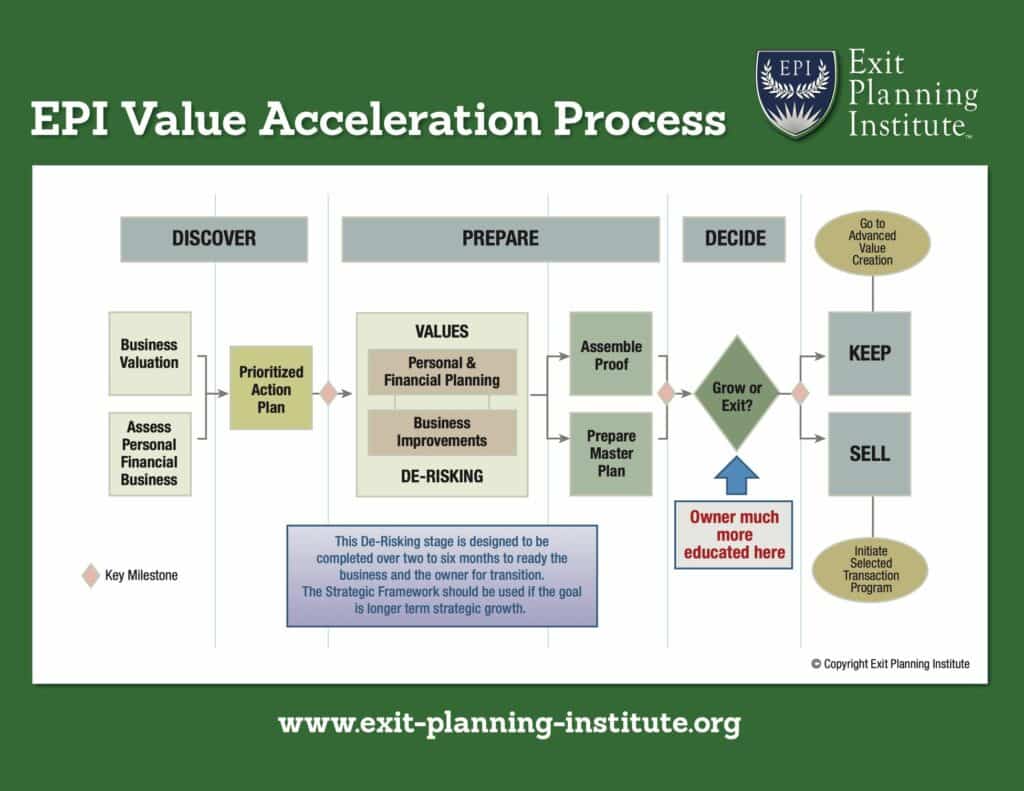

In Part I Exit Planning we know that many companies fail to sell or get a fair price because they are not ready. Readiness includes documentation. There is a whole step in the Value Acceleration Methodology(c) around this called “Assemble Proof”, see below.

Figure: Value Acceleration Methodology(c)

Source: Exit Planning Institute

You will need to go through increasing levels of document disclosure with the most disclosure at the final due diligence stage. If you have gone through the exit planning process you will have compiled all this information already. If not, the time is nigh. You will need annual reports, financial projection, customer report showing concentration (customer name kept confidential initially) and contracts, supplier concentration and contracts, revenue by category and geography, AR and AP ageing reports, inventory reports including obsolescence, fixed asset schedule, and personnel and contracts, and more, much more.

You need to anticipate what buyers will ask and have the answers in your information. As time goes on the advisor will compile FAQs, a running document that answers the common questions upfront.

You may have a staggered approach with some information provided early (e.g. annual reports), more provided mid-process with some interested buyers, and the most sensitive not shown until the very end of due diligence e.g. customers and contracts.

You will also show the business plan and performance, sales and marketing plan and performance, and other department plans. You’ll need to show and explain growth opportunities, growth and maintenance capex, and working capital requirements. The financial model will help show this. If you’ve gone through the Strategic Framework with a CEPA this will be ready to hand over—and will help sell the company.

You may not provide any detail to some prospective buyers (e.g. competitors) until due diligence, in other cases you may provide everything upfront (e.g. reputable private equity firms).

Documentation is probably held in a digital folder system with tight permissions called a virtual data room. Or you may choose to use a physical room where buyers can enter without a camera for a day (less likely nowadays).

Companies may also do what is called a Quality of Earnings Report, commissioned from an independent accountant. This is a form of audit that makes a judgement about current earnings and the prospects and risks of future earnings. This is not a cheap report and tends to be only done where the business and transaction size is sufficiently large to justify the expense. It is well worth the expense though because it gives buyers confidence and can show issues that may not have been thought about during the readiness preparation phase.

You should prepare all these documents before going to market so you do it on your timetable not at the last moment while you juggle operating the business leaving the buyer to wonder what’s taking so long.

Sales Material

The advisor will now give the business owner three documents to approve:

• Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA),

• a pre-NDA “blind teaser” or summary

• a post-NDA information memorandum (IM)

The NDA is a legal document signed by the buying promising not to reveal confidential information. In theory, they could be sued for damages should it be proven they breached this legal agreement.

The blind teaser is 1-2 pages describing the business but not identifying it. It kicks off the sale process when its sent to potential buyers.

The IM discloses the company name and provides sufficient information for the investor to decide as to whether the company is worth investigating. It will cover the products and services, customers, channels, operations, organisation chart, competitors and industry. It will have financial statements and projects, growth opportunities, the reason for selling, systems showing transferability.

It may be in a slide deck or word document format. Much of the information may be in appendices. It will describe the process and a tentative timeframe with clear next steps.

The Approach

The advisors will contact the people on the buyers’ list, give the prospective buyer the blind teaser and, if they’re interested, send them a Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA). Once the NDA is signed the Information Memorandum is sent.

Most often there is a period of intensive follow up by the advisor to see if the buyer is interested and answer preliminary questions. The advisor also takes this chance to highlight the strengths of the business.

Ideally, buyers will be aware of a certain timeframe to a) express interest and later b) make a non-binding offer. If the mid-market business is very appealing the buyers may stick to the timeframe but chances are the timeframe will slip.

In small businesses, advertising to private buyers is key. They can’t identify many of the likely buyers so it is a requirement. It may also be worthwhile approaching strategic buyers. Private equity firms are an unlikely choice given their investment parameters include EBITDA of $5M plus.

The Investigation

At some stage, the M&A advisor has answered all the buyer’s questions the advisory is willing or able to, including providing access to all or part of the virtual data room. The buyer will now need to talk directly with the business owner and visit the site(s).

The buyer will press for more information to assess the risks and opportunities of the business, some of these are acceptable, others will need to be deferred until due diligence (should that proceed).

The M&A advisor will be trying to understand the buyer’s acquisition objectives and how the business helps achieve those objectives. Many of these buyers will not proceed to make an offer, often for reasons nothing to do with the owner’s business. See more on buyers in Chapter 22 Understanding Buyers.

The M&A advisor will want to understand how the buyer will finance the acquisition including equity, bank debt, or reliance on vendor financing. This should be outlined in any offer and the M&A advisor may confirm directly with the financier.

The Offer

In NZ, the first offer is called “Heads of Agreement”, “Term Sheet” or “Non-Binding Indicative Offer” (NBIO), or such like. It includes a price range and terms and is at least reviewed by lawyers if not written by them. It is conditional on many things but certainly more investigation and a level of due diligence (DD). Note a lawyer will clearly state what is non-binding e.g. the price, and what is binding e.g. confidentiality.

Sometimes, after further investigation post the first offer, a revised offer is made but this time with a binding price and terms but still conditional on due diligence. It forms the draft document for the larger legal document next. In the US this is called a “Letter of Intent”.

Post-NBIO being agreed and any conditions being satisfied, a final Sales and Purchase Agreement is then negotiated with no second binding offer. Regardless, once we’ve reached this stage the lawyers becoming heavily involved and write the document.

At some stage, the buyer will insist on an exclusivity period. Whether this is granted is a key decision to be made and is much about the period of exclusivity as the exclusivity itself.

In a New Zealand small business sale, handled by a business broker, there is probably no “Non-Binding Indicative Offer”. Instead, the parties will go straight to a Sales and Purchase Agreement (SPA). This is partly because NZ has a widely accepted standard template from the Auckland District Law Society and REINZ. The lawyers still become heavily involved but many of the key terms are standardised.

In Australia, small and mid-market business sales tend to have NBIOs followed by a sale and purchase agreement. In the US, mid-market sales have an Indication of Interest followed by a Letter of Intent (two stages New Zealand wraps up as one) and finally the sale and purchase agreement.

Auction Process

There is a sales process continuum. At the one end is the auction where many investors are invited to bid for the business. They are often provided with deadlines and terms and conditions in a set auction process. This is most often used for listed companies or mid-market companies with a great deal of interest.

On the other end of the continuum is the limited negotiated sale where only one or a few parties are invited to discuss buying a company. Everything is negotiable including the deadline. This might be the case where this is only a limited number of potential buyers.

For New Zealand mid-market business its somewhere in the middle. Very few business sales stick to a controlled auction process probably due to the smaller number of investors. In the US there is a deeper pool of private equity and trade buyers which means more competition for offers and a reluctant buyer acceptance of a controlled auction process with deadlines.

Instead, a managed auction process is used where the M&A advisor provides only tentative deadlines until such a stage that there are multiple offers. Only then are deadlines for offers instituted. (Note Business Brokers must follow a regulatory mandated “Multi Offer” process if they have two or more written and signed sale and purchase agreements).

The aim is to approach different buyer types at different stages such that they make offers at about the same time. A Japanese multinational makes much slower decisions than a private equity firm. The M&A advisor will approach the slow decision-makers first before the quick ones. This is very much the art of M&A, it is very difficult to “herd cats” so to speak.

I don’t recommend contacting only a small number of likely buyers, this limits competition and you could be left with no one making an offer. On the other hand, we don’t recommend contacting everyone on a long list of buyers immediately. It becomes unmanageable especially with lots of tyre kickers or information thieves i.e. competitors trawling for information.

Sure some M&A advisors run a strict auction process where all the buyers know the deadline to put in a bid along with their comments on a suggested sale and purchase agreement. The problem is many companies regard this process as a waste of their time, there is lots of effort and expense in making an offer, and too many buyers scares some companies away.

I recommend a managed auction process also called a modified or limited auction. This is an auction that is not an auction, or at least isn’t presented as an auction to the buyers. The M&A advisors will work their way down the buyers’ list generating sufficient interest so they have at least two bidders that have made an offer at about the valuation or above who can show they have the financial resources to complete any sale.

NBIOs will be considered and negotiated, especially any period of exclusivity. If the buyer is reputable, the terms are acceptable, the next information requests seem fair (pre-due diligence), buyer financing is believable, and the period of negotiation exclusivity appropriate then the buyer and seller will move to the next stage. This may involve more than one buyer for a highly sort after business.

The buyer(s) will analyse the provided information. At this stage, they will either demand full due diligence before preparing a sale and purchase agreement. Or they will make a sale and purchase agreement conditional on due diligence. If they are not a competitor then proceeding with due diligence (DD) at this stage may be acceptable. If they are a competitor then limited DD will be allowed with key information not revealed until the very end of the process.

Due Diligence

You’ll need to open the books to the selected buyer. You’ll field many questions during this time so make sure you, the finance manager and someone else has time free to assist.

There will be legal due diligence (DD) looking for all the relevant documents covering customers, suppliers, employees, IP as well as on the hunt for any outstanding lawsuits and other risks.

There will also be an accountant due diligence where they will be looking at the quality of earnings and other financial risks.

Most business owners have little to hide but occasionally DD will pick up something. Here are two ways (Hinson).

1. Creating income by changing an accounting principle. For example, an allowance for bad debt. The seller could reduce their bad debt % from 5% to 2% of gross accounts receivable, thereby releasing income by the difference of 3% the into the accounts receivable.

2. Delay expenses through capitalisation. When you capitalise something on the balance sheet you recognise the cost over future periods. The P&L impact would see lower expenses spread out rather than one large hit in the particular P&L period. A dodgy business owner may make a normal expense into a fancy asset.

Having followed an exit planning process you will be completely ready for this frankly onerous process. If you have done a Quality of Earnings report as well then this process should result in no issues.

Sale and Purchase Agreement

If the business is not ready for sale, the buyer will find undisclosed issues, become unsettled about the lack of disclosure, and get frustrated at the length of time to get requested documents.

If they find major issues, they will reduce their price, known as a “retrade”, or walk away from the deal. It is important to keep all the other buyers informed of the process so they can become engaged again should this happen.

If you reach final agreement then a completion (i.e. settlement) date will be set.

Closing

The M&A advisor will drive the closing schedule, making sure all parties are keeping to agreed deadlines for their respective tasks.

The lawyers will work with the business owner, buyer and intermediaries on the settlement statement. This shows the source of funds and use of funds. The funds flowing from the buyer and buyer’s bank through the lawyers’ trust accounts to the owner (and the owner’s bank if applicable).

The buyer may provide a certain amount of equity and the buyer’s bank a certain amount of debt. The funds are used for the purchase price, working capital, and M&A expenses.

The seller would see that the purchase price less any debt, less any working capital adjustment, less bank debt and deposit.

Each party would see their respective expenses with the seller’s professional advisors being paid out of the purchase price.

Delayed Payments

The more risk a buyer sees in the business, the more they will want the business owner to carry that risk. This might be through payments contingent on financial performance called an “earnout”. These are funds that are held back by the buyer and are contingent on future performance. They may be put into a lawyer’s trust fund for seller’s peace of mind.

Or it may through vendor financing where the business owner provides a loan to the business on standard commercial terms. The security is the business so if it fails the business owner may take back the business (ignoring other senior debt obligations).

Exit planning and a good M&A process aim to avoid these contingent payments. Sometimes it needs to be used to bridge a price gap between the parties.

Small vs Mid-Market Business

The business sale process for a small business can be significantly different from a mid-market business.

This is due to the buyer type. Where you can identify a buyer you can contact them directly e.g. industry corporates and private equity firms. Where you can’t, e.g. small private buyers looking to “buy a job”, you will need to list the business for sale.

It can also be due to deal size. A CEO, corporate development manager or private equity manager will have limited capacity, they can only analyse and process so many deals every year. They need the deal to be of sufficient size to be worth their while and make a significant impact on their company’s financial performance.

Also in relation to deal size is the extent to which a company can insist on having a deadline auction process where buyers must make offers within a timeframe. Larger companies are sufficiently attractive for buyers to agree to this process. Small companies deadlines tend to be simply ignored even if they are instituted. Mid-market companies in NZ, unlike the US, most likely will also struggle to get buyers to follow a deadline process.

These are no hard and fast rules, some companies that are on the margins of mid-market may also benefit from listing their business, and small ones may benefit from direct approach especially where they offer unique technology or competitive advantage.

What’s a mid-market business?

It’s probably best to identify small and large first. In my opinion, a small business arguably has revenue below $5M, is owner-operated, with fewer than 20 employees and EBITDA less than $1M.

From an M&A perspective, a large business is arguably one that could be listed on the stock exchange. This probably means market capitalisation should be at least $100M and probably $200M. This probably means its EBITDA is more than $20M and certainly more than $10M, and revenue is $100M to $200M. Employee count may be more than 20 and less than 100 (or possibly 200).

GE Capital (2014) put out a report that states NZ mid-market revenue lies between $2M and $50M. It says the mid-market is 6.5% of NZ businesses they make up 32% of NZ’s sales, have an average of 23 employees and $5 million of annual revenue. About 35% are in Auckland, 11% in Wellington and 14% in Canterbury, with the rest spread across New Zealand.

Grant Thornton (2019) put out a report that suggests revenue of between $5 million and $30 million and/or between 20 and 99 employees. On this basis mid-market is 2.2% of businesses (10,700), account for 17% of business revenue and 21 % of employment. About 38% of business are 21 years or older.

From an M&A perspective, I believe the upper range is too low. A New Zealand mid-market company has revenue between $10M and $100M with likely EBITDA of between $1M and $15M. If it’s less than this then the buyer type will likely include small private buyers with the accordingly adjusted sales process. If it’s more than this then it could possibly list on the NZX.

Want to read the following chapters? Please purchase How to Sell a New Zealand Business with ‘No Regrets’.